The Industrial Revolution Ran on Water

This post is part of our History of Water Supply series

The Industrial Revolution was a period of major technological and social transition, and in some ways its transformative effect is owed to water: the steam engine almost single-handedly kicked off the Industrial Revolution by allowing for powerful and scalable mechanical energy. By the early 1800s, European cities were growing faster than ever as populations swelled around factory hubs. This urbanization had a tremendous impact on water and water supply as cities came under unprecedented resource strain.

In order to meet exploding demand, administrators began pulling water from every possible source: they redirected rivers, built reservoirs, and dug enormous wells. And because the demand for water was so large and unrelenting, stoppering its flow was unthinkable. Recognizing this monumental role of water in modern urban life, some of the foremost scientists of the day set out to better understand it.

Isaac Newton had opened the debate by describing the first formulas on the relationship between viscosity, flow, and friction in the movement of water. Building off his work, Gotthilf Hagen and Jean Poiseuille added the role of pressure into the equation: Using their updated formula, engineers were able to plug in the variables of a pipe’s length and diameter combined with water pressure to obtain the exact flow rate in a system. This development proved to be an essential formula for understanding how water moved and, therefore, for measuring and controlling how it moved in early modern water systems.

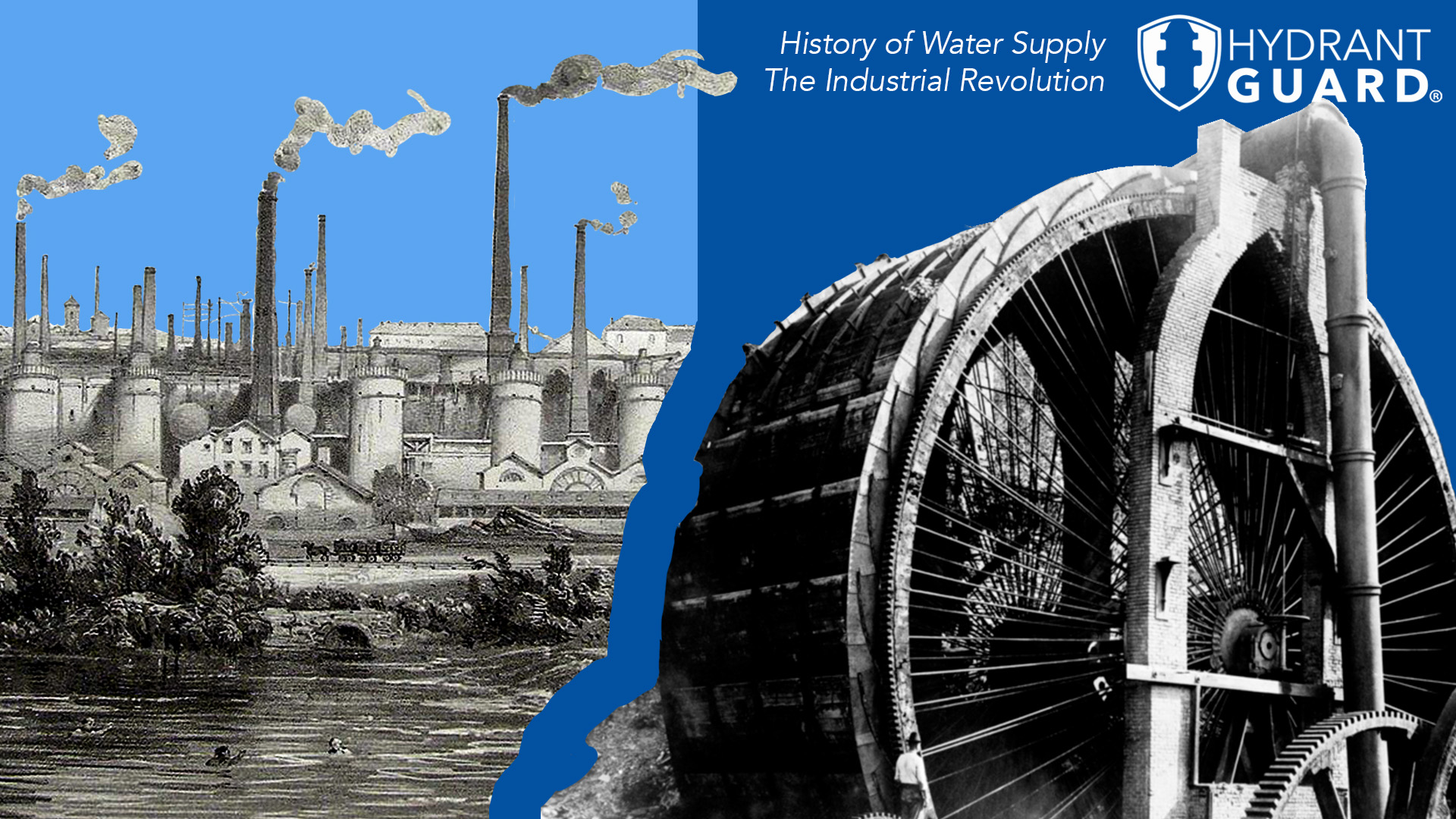

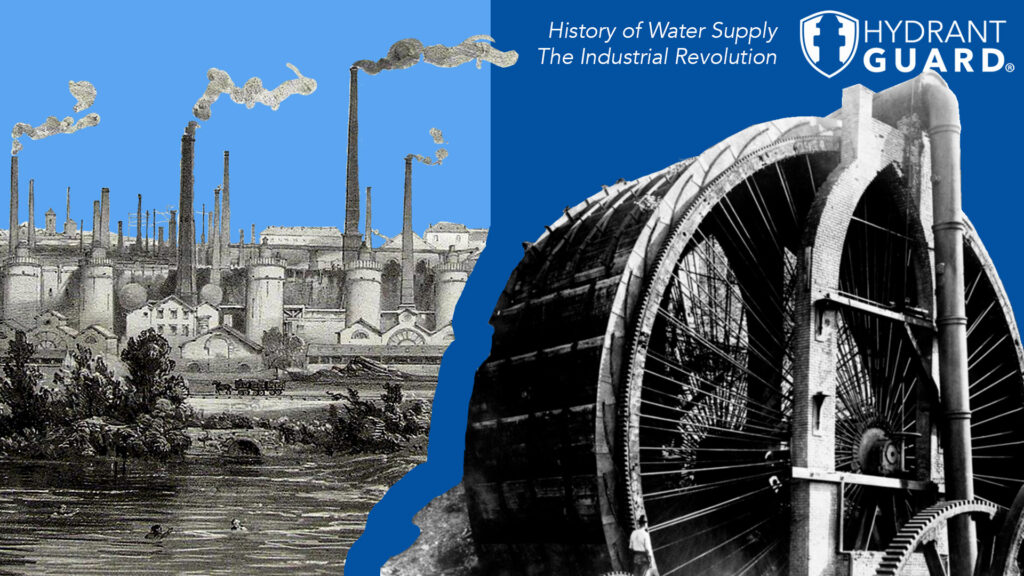

In the industrial world, entrepreneurs were harnessing water’s newfound potential. Installations like waterwheels and watermills had been around for centuries, channeling water’s kinetic energy to perform simple tasks like grinding grain or sawing wood. But now, steam was powering ships and trains, and soon steam-powered turbines were generating electricity – an innovation that turned cities into roaring, round-the-clock urban centers.

Unfortunately, people were largely unaware of the consequences of excessive water use and inadequate waste disposal. Waterborne diseases began to tear through overcrowded, under-resourced cities. Stepping up to this challenge, a new generation of scientists set out to discover what’s inside water and experiment with new ways to sanitize it. In our next installment, we’ll look at these efforts and the countless lives saved by effective water treatment.

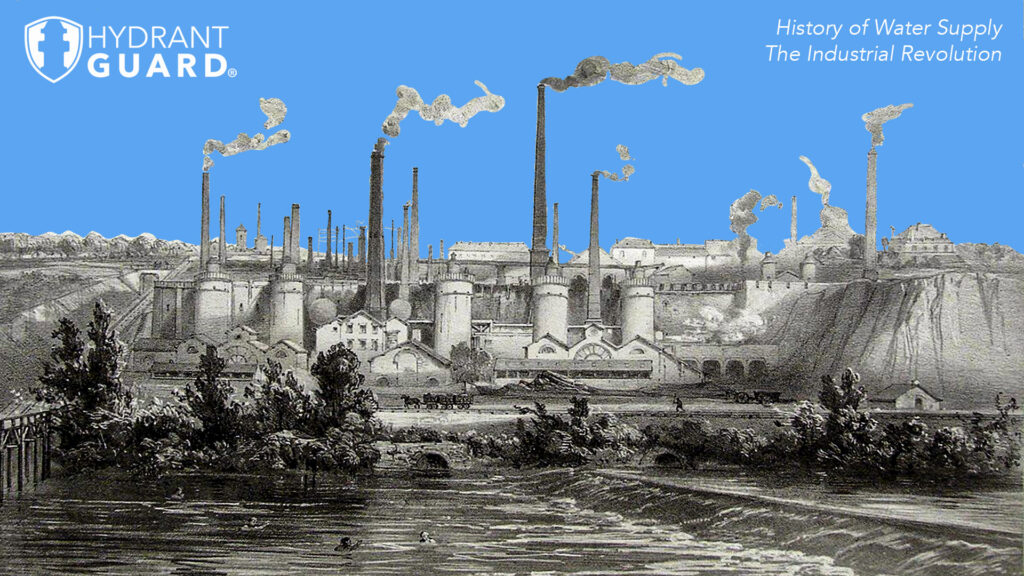

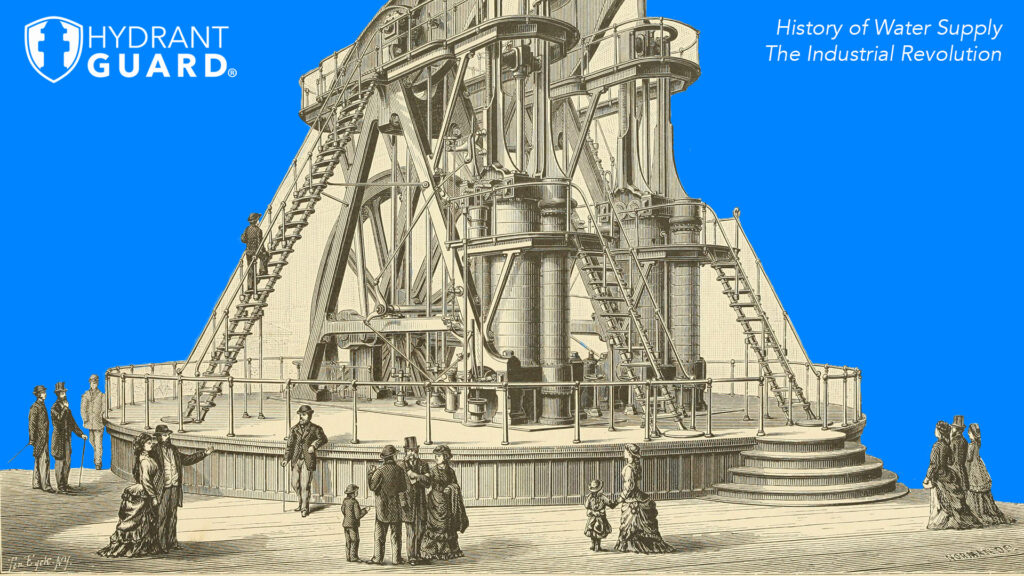

Pictured below, left to right: blast furnaces at Commentry in 1856; the Corliss beam steam engine; the Burden Water Wheel